(Addendum added at the end)

I can’t offer much in the crowded field of Disney gender criticism. But I do want to update my running series on the company’s animated gender dimorphism. The latest installment is Frozen.

Just when I was wondering what the body dimensions of the supposedly-human characters were, the script conveniently supplied the dimorphism money-shot: hand-in-hand romantic leads, with perfect composition for both eye-size and hand-size comparisons:

With the gloves you can’t compare the hands exactly, but you get the idea. And the eyes? Yes, her eyeball actually has a wider diameter than her wrist:

Giant eyes and tiny hands symbolize femininity in Disneyland.

While I’m at at, I may as well include Brave in the series. Unless I have repressed it, there is no romance story for the female lead in that movie, but there are some nice comparison shots of her parents:

Go ahead, give me some explanation about the different gene pools of the rival clans from which Merida’s parents came.

Since I first complained about this regarding Tangled (here), I have updated the story to include Gnomeo and Juliet (here). You can check those posts for more links to research (and see also this essay on human versus animal dimorphism by Lisa Wade). To just refresh the image file, though, here are the key images. From Tangled:

From Gnomeo:

At this point I think the evidence is compelling enough to conclude that Disney favors compositions in which women’s hands are tiny compared to men’s, especially when they are in romantic relationships.*

REAL WRIST-SIZE ADDENDUM

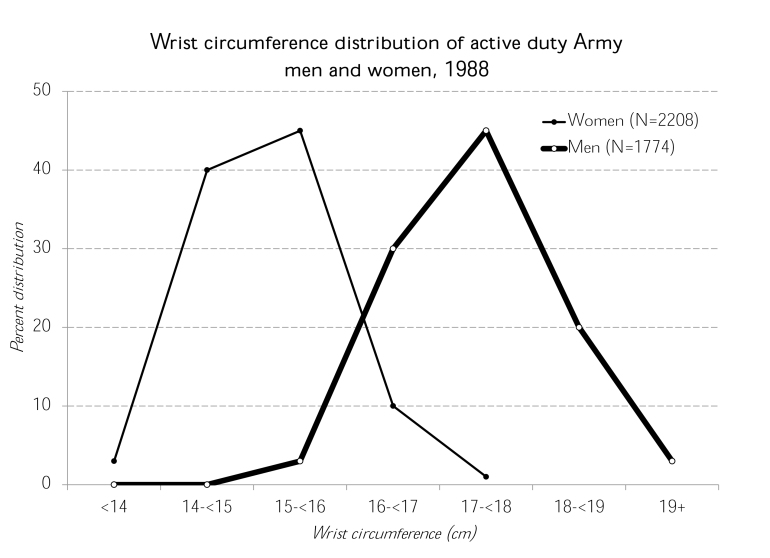

How do real men’s and women’s wrist sizes differ? I looked at 7 studies on topics ranging from carpal tunnel syndrome to judo mastery, and found a range of averages for women of 15.4 cm to 16.3 cm, and for men of 17.5 to 18.1 cm (in both cases the judo team had the thickest wrists).

‘Then I found this awesome anthropometric survey of U.S. Army personnel from 1988. In that sample (almost 4,000, chosen to match the age, gender, and race/ethnic composition of the Army), the averages were 15.1 for women and 17.4 for men. Based on the detailed percentiles listed, I made this chart of the distributions:

The average difference between men’s and women’s wrists in this Army sample is 2.3 cm, or a ratio of 1.15-to-1. However, if you took the smallest-wristed woman (12.9 cm) and the largest-wristed man (20.4), you could get a difference of 7.5 cm, or a ratio of 1.6-to-1. Without being able to hack into the Disney animation servers with a tape measure I can’t compare them directly, but from the pictures it looks like these couples have differences greater than the most extreme differences found in the U.S. Army.

*This conclusion has not yet been subject to peer review.

Is this not the one of the same reasons many people (mostly women?) love Dirty Dancing? The size of Patrick Swayze’s hands against her little itty bitty waist.

You previously talk of this being a patriarchal norm. Would you be able to describe what a matriarchal norm would look like in this space?

LikeLike

I think that’s like asking what a socialist norm is in capitalist society. No, I don’t know of any matriarchal norms.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The Iroquois were a matriarchal society, as are the Hopi and some Tibetans. There are no physical norms, only social and governmental.

LikeLike

No matriarchies, ever, according to Steven Goldberg (“Why Men Rule”). There were some very, very small cultures, possibly, that had no real heirarchy, but no matriarchies.

LikeLike

I’d have to say that PSdan is reading things from an ignorant place. There were several Matriarchal tribes in Native America. And there was no really “size” or physical normals for them. Only their social and government role and how they played them. The women were the brains and decision makers, and the men were their defenders and voices.

LikeLike

Isn’t the whole point of caricature to exaggerate differences? It’s not incorrect to note differences between purposive dramatization and statistical reality, but it is incorrect to suppose that social stories and their ideal types are ever, or should be, scientifically representative.

LikeLike

Someone always says this. It’s a perfect example of the absence of sociology. Of course cartoons exaggerate. (And they aren’t limited to exaggerating things along some reality continuum. For example, Frozen exaggerates how much snowmen and reindeer talk.) That’s what makes it interesting sociologically: they don’t exaggerate everything, which I think would be mathematically impossible. So, what do they choose to exaggerate? They could have exaggerated the number of African immigrants in Norway. The consistent choice to exaggerate the body differences between men and women in positively-depicted relationships indicates that this trait is normatively desirable, and Disney is promoting it. I am not arguing cartoons “should” be realistic. I am pointing out the values exhibited by the choices they make.

LikeLike

That’s absolutely correct. In fact while I was writing my post I had a little analytical dialogue going on in my head, imagining recent caricature drawings I’d seen, and realizing that caricature artists “capture” or “frame” a subject by exaggerating already-salient and a-modal characteristics of a person. Cartoons and other social stories select salient details and suppress others in order to construct and maintain ideal types.

I don’t know where I land on gender neutrality and heteronormativity and such – haven’t thought about them a ton. I suppose at least personally I try to cultivate, and live amongst friends who cultivate, the expression of androgyneity and a mix of gendered expressions. But I don’t see anything wrong with the presentation of categorical ideal types, as long as children also get the message that it’s perfectly fine to remix those categories how they want as they grow.

I suppose I’m drawing on kind of a larger philosophical disposition I’ve been finding myself settling in to, giving up the game on searching for equality, homogeneity, and neutrality of social contexts, outcomes, and characteristics, and deciding that what’s important more so is movement between and among the social categories and boundaries that exist.

LikeLike

“The consistent choice to exaggerate the body differences between men and women in positively-depicted relationships indicates that this trait is normatively desirable, and Disney is promoting it.”

But IT IS DESIRABLE. That’s the whole point!

Do I like boobs? Yes. Do I like BIGGER BOOBS? Hell yes! Should Disney make boobs bigger, so I’ll like their movie more? Hell yes, if they want my money, and of course they want my money, but there’s other factors they have to take into account, for example, the fact that their movies are family friendly, so they can’t exaggerate something like boobs, BUT, they can still exaggerate something desirable, like her small body frame.

LikeLike

I can’t offer much in the crowded field of Disney gender criticism.

Perhaps that crowded field should ask itself if it is fundamentally anti-human. Disney has been phenomenally successful not because its business plan boiled down to “perpetuate the hetero normative patriarchy”, but rather because it continually makes movies people want to see. The stories and images resonate with humans, not gender studies departments.

You can check those posts for more links to research (and see also this essay on human versus animal dimorphism by Lisa Wade).

That has to be the most superficial writing on dimorphism that I have ever read. The kind that matters is the human kind; whether other species exhibit it to a greater or lesser extent cannot possibly inform human dimorphism. That Lisa spends so many words on that irrelevant digression means she cannot address anything more than cherry picked human examples.

Like voice, for instance:

There are many more such examples, but the fact that Ms. Wade couldn’t spend a syllable on this or similar obvious and distinct differences isn’t a good sign.

The consistent choice to exaggerate the body differences between men and women in positively-depicted relationships indicates that this trait is normatively desirable, and Disney is promoting it.

Why pile on Disney?

Queen Nefertiti could have been a Disney female lead. Hindu statuary could scarcely be accused of failing to exaggerate dimorphism.

LikeLike

Jeff,

Here is why Disney is facing criticism when there are other examples of similar representations of women in other cultures and religions (like Nefertiti and Hindu statuary) that don’t receive the same kinds of criticism.

First of all, it’s possible that as artworks they ARE subject to criticism. I am not an academic historian of art, but I can tell you that artworks are examined critically using a variety of viewpoints and philosophies in their cultural contexts. Culturally, though, I would say that images of Nefertiti and Hindu statuary serve a different purpose. No one in Nefertiti’s time who saw her image was publicly aspiring to be her. Disney deliberately sets girls up to aspire to be a princess in order to sell lots of stuff with princess images on it. They aren’t shy about telling you this. They’re in it to make money and they snag stories in the public domain and cultural norms that people are already familiar with. They do this to entertain, but also to make money. For the most part, that doesn’t make for adventurous storytelling, and in the case of Frozen, where they did take some risks with structure and message, they still couldn’t get past cultural norms of what girls and women should look like, ideally.

In today’s world, Nefertiti and Hindu statuary aren’t ubiquitous. Images of them do not appear on children’s (or adults’) underwear, girls aren’t faced with racks of Nefertiti and Hindu statuary costumes with short skirts and without many other choices at Halloween, they aren’t part of children’s daily media consumption that feeds them the idea that the ideal career for a girl is ‘princess’ and princesses have to be rescued. The concept girls in the United States have of royalty does not include Kate Middleton, Eleanor of Aquitaine, or Elizabeth I. Princesses here are Disney princesses, and they are presented with impossible figures. Even if parents aggressively work to keep Disney princesses out, they are everywhere, and sometimes (as with the aforementioned underwear) they are the only choice on the shelf.

I really liked Frozen, but I also think it’s flawed. I would say that the princesses in Frozen are the most exaggerated examples of the tiny waist/gigantic eyes combination I have seen yet in a Disney movie. This is supposed to be about sisterly solidarity,love and sacrifice, Why is it that the most powerful song in the movie, about claiming your gifts and celebrating your identity, ends with the main character in a dress slit thigh high? Who is she dressing for? She’s completely alone on a mountain, singing about how great it is to “let it go”. There’s no freedom in wearing a dress like that. If the target audience for the movie is little girls, what message does it really send about being yourself?

If girls had lots of different kinds of role models presented to them constantly in the media, Disney princesses probably wouldn’t be as big a deal, because they’d be a small part of what girls experience. But the images presented to them constantly in the media are Disney princesses. My daughter tonight, told me she loves presidents, but that women can’t be President, only First Lady. Wouldn’t it be great to see Disney change the princess ideal they’re selling now to one that presents a vision of what a capable girl can become?

Disney is a gigantic corporation, publicly owned. As consumers and possibly stockholders, the public has every reason to be concerned about what, and how, it is selling. And that’s why people pile criticism on Disney.

LikeLike

Much as the disneyfication of male/female dichotomy distresses me, we certainly have a good real-life example of vast hand-size difference in princes and princesses!

LikeLike

I got owned.

LikeLike

It’s stylization, plain and simple.

LikeLike

Large eyes are designed to exploit the human tendency to find that trait endearing as it resembles infantile features.

Her eyes were intentionally increased in size to make you love her more.

LikeLike