Everyone is excited by the decline in the teen birth rate in the US. But And here are a few things you should know about it.

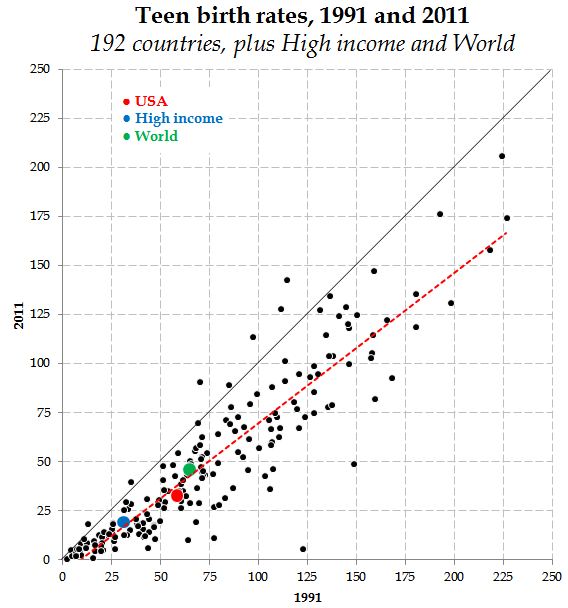

This chart shows the birth rates for women ages 15 to 19 in 192 countries, plus the world and the UN-defined rich countries, for 1991 and 2011. Dots below the black line show countries where the teen birth rate fell. The red line shows the overall relationship between 1991 and 2011. Dots below the red line had greater than expected reduction in teen births.

Source: My graph United Nations data.

The chart shows four things:

1. Teen birth rates are falling globally. From 1991 to 2011, the birth rate for women ages 15 to 19 fell from 65 to 46 births per 1,000 women worldwide.

2. US has higher teen birth rates than any other rich country. At 33 per 1,000, the US has more teen births than Pakistan (28), but fewer than India (36). For high income countries, by the UN definition, the rate is 19. The rate for the Euro area is 7.

3. The teen birth rate is falling faster in the US than in the world overall. The world rate fell 29% from 1991 to 2011, while the drop in the US was 44%.

In the US, there are a lot of factors related to falling teen births. But they’re mostly about how it’s happening, not why it’s happening. For example, Vox published a list of factors, as did Pew before them, that are reasonable: the recession, more birth control, more Medicaid money for family planning, cultural pressure, and less sex.

But to understand why this is happening, you have to stop thinking about teenagers as some sort of separate subspecies. They are just young women. Soon they will be in their 20s. The same women! So the short answer for why falling teen birth rates happening is this:

4. Teen birth rates in the US are falling because women are postponing their births generally.

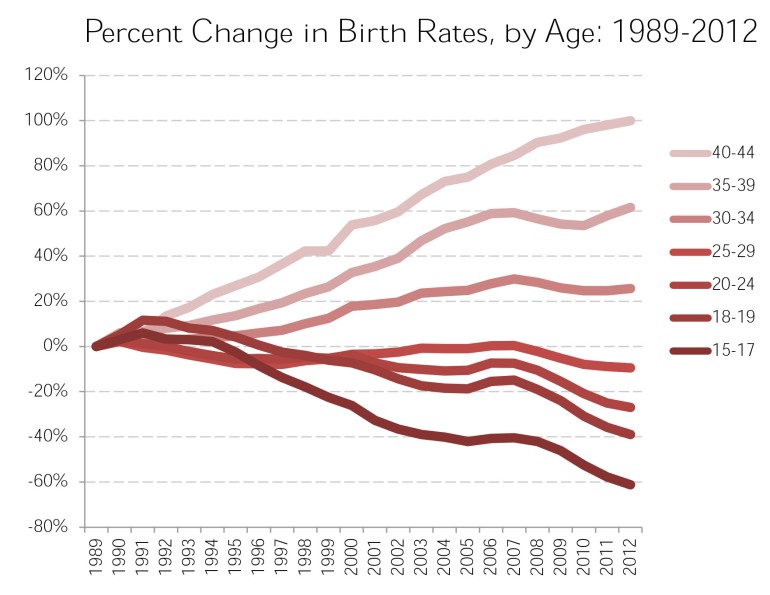

You can see this if you line up teens next to women of other ages. Here are the changes in birth rates for women, by age, from 1989 to 2012.

Source: My graph from National Center for Health Statistics data.

See how the trend for the last decade is parallel for 15-17, 18-19, and 20-24? As those rates fell, birth rates rose for the 30+ community. The younger women are, the fewer births they’re having; the older they are, the more births they’re having. Teenage women are women! They do it for all the reasons it’s happening around the world: some because they are delaying marriage, some to pursue education and careers, some to see the world, and so on.

Here is another way to look at this. Here are the 50 US states, from the 2000-2012 American Community Survey. This shows that states with lower teen birth rates (those are per 100, on the y-axis), have higher birth rates for 25-34 year-old women relative to 20-24 year-old women. I’ll explain:

Where more women have children ages 25-34 relative to 20-24, there are fewer teen births. So, in Alabama, about 3% of women 15-19 had a baby per year, and in that state the birth rates are about the same for women 25-34 as 20-24. Alabama is an early-birth state. But in New Hampshire, only 1% of teens had a baby, and women 25-34 were almost 2.5-times more likely to have a baby than women 20-24. New Hampshire is a late-birth state. What’s happening with teens reflects what’s happening with older women.

To some significant degree, it’s not about teenagers, it’s about women delaying births.* I would love it if reporting on teen births would always compare them to older women.

*Notice I didn’t just exaggerate and say, “it’s not about teenagers.” I added “to some significant degree.” That’s the difference between a post that is selling you (your clicks) to someone versus a post that’s trying to explain things as clearly as possible.

Yes, the time-lag phenomenon is ongoing. Here’s a piece I wrote about it in 2012 called Babies on Hold

http://rhrealitycheck.org/article/2012/10/06/babies-on-hold/

and in 2013 – Older Women Having More Kids, Younger Ones Still Having Fewer

http://www.domesticproduct.net/?p=1469

The chart in the 2013 piece shows the upturn in births among women 30+ following the recessionary fall in all births. I’ll update that chart with the 2013 data soon – it is all part of the delay trend that began in the US in 1960 and has been growing ever since, as women invest more in their educations and careers and in participating in policy making, within a culture of lowered demand for workers, effectively becoming the workers their unborn male children would have been 100 years prior.

LikeLike

Great stuff. One question; do the changes in age at first birth differ by race at all?

LikeLike

meanwhile unintended pregnancies and births have been rising…particularly for lower-income women…

LikeLike

How do you know that? pregnancies and child birth rates of people of all incomes have been flat or dropping slightly. For that matter, fertility of poorer Hispanics and blacks have been dropping.

LikeLike

Vijay, although birthrates and teen-birthrates have been declining, some evidence suggests that “unintended pregnancies” have been falling among women with higher incomes/better education, and increasing among women with with lower incomes/less education. For example, this study shows unintended pregnancies between 1981 and 2008.

http://www.guttmacher.org/pubs/FB-Unintended-Pregnancy-US.html

I’m sure there are studies with more recent rates, but this is perhaps an example of what Celeste is talking about. I would disagree with her that unintended pregnancies/births have been rising in the aggregate, but it looks like they may be rising among the particularly poor.

LikeLike

My point was that, both the Gutmacher study and http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3338192/ show that unintended pregnancies have been dropping and flat from 60 to 40 (per 1000) since 1981. Hence the first part of the statement is untrue.

regarding especially the lower income women, the analyses need to separate out by race. Historically, the lower income segment has had higher unintended pregnancy rates; Black and Hispanic women have been 2.5 to 5 times the rate of unintended pregnancies. The clustering of the unintended pregnancies by income is circular, propelled both by race and poverty.

Blanket statements like “meanwhile unintended pregnancies and births have been rising” are untrue.

LikeLike

Vijay — the most recent data indicates that the US unintended pregnancy rate rose in the aggregate between 2001 and 2008 (see Finer and Zolna 2014). As for unintended births, the most recent data shows that the percentage of all US births that were unintended dropped from the early 1980s to the early-mid 1990s but has been rising since. In 1995, 30.6% of births were unintended, in 2006-2010, 37% of all births where unintended (see Mosher and Jones 2012, p. 17).

As for race, the Mosher and Jones (2012) study shows that the unintended birth rate has risen for both NH-Whites and Blacks since 2002 (see. p. 20).

I find it odd that you accuse Dr. Cohen of disregarding the efforts of the CDC or other state agencies in reducing teen and/or unintended births. He does not do this — he recognizes that these programs are in fact reasonable explanations for PART of the reduction in teen births. His overall point is simply that you can’t understand what is going on with behavior of teens without understanding the overall demographic transition process that is shaping the fertility behavior of US women as a whole (and not just US women — because, as he shows — this is occurring across many countries!). An important insight here is that unintended pregnancy and births have not gone away, they have just shifted to somewhat older women. If we believe unintended pregnancies and births are best avoided but we can’t see this because we are too preoccupied with the behavior of teenagers, there is a problem — no? The point is, fertility/marriage/family formation postponement means that women are at risk of unintended pregnancy and birth for a longer portion of their lives. In my reading of the public health literature on unintended pregnancy, there is too little attention paid to the contribution of overall demographic transition processes on changing fertility behavior and risk. An integration of these insights would strengthen the work of state agencies and the CDC. I don’t see this as a challenge, but as a valuable insight and potential corrective.

References here:

Finer, L. B. and M. R. Zolna (2014). “Shifts in intended and unintended pregnancies in the United States, 2001–2008.” American Journal of Public Health 104(S1): S43-S48.

Mosher, W. D., J. Jones, et al. (2012). Intended and unintended births in the United States: 1982-2010, US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics.

LikeLike

Well put!

LikeLike

OK, place yourself in CDC and state agencies place. Postponing teen births is a topic that the public, political parties and the government has developed a common cause. The child birth characteristics of adult women are not something (intended or unintended) the public would like CDC to get involved in. How would you or DR. Cohen like it if CDC sets a goal in reduction of adult women pregnancies intended or otherwise. My point is adults are adults, they can choose to be pregnant when they want or without intention.

These sentences slay me “fertility/marriage/family formation postponement means that women are at risk of unintended pregnancy and birth for a longer portion of their lives”. No! they are not! Contraception and abortion is available in the US. All women, whether they have children at teenage or not, have similar risks of unintended pregnancy unless you make the assumption that once they have children they desist from all forms of sex.

My only overarching conclusion is that there has been a reduction in fertility since say Mid-90s; and this has been driven in reduction of teenage pregnancy; which in turn, was driven by common goals of public, government and agencies. The first figure makes it appear that the rate at which women have later child births is comparable to the reduction in teenage births; simply, the good professor has chosen the axes in a manner of his liking.

LikeLike

All Dr. Cohen is doing is trying to help explain what is really going on. I don’t see a call to arms against the agenda of the CDC or any state agency anywhere in his writing. As for myself, I personally think reducing the teen birth rate is a valuable policy goal – not because the data are entirely clear that avoiding a teen birth improves the economic position of individual women (it isn’t) but because it reduces public expenditures and it probably does help some young women finish their high school education. It also likely helps non-teen women avoid unintended pregnancies and births even if these women receive very little public attention. As for whether the public wants to take up the policy goal of helping non-teen women reduce unintended pregnancies and births in a more direct manner is for the public to decide (and many people do support this), but they are unlikely to approve of measures to do this if they do not even understand what is going on. And the government is not the only way to address this issue — private actors and organizations have historically played an important role in advancing contraceptive access and educating the public about reproductive health, rights, and women’s issues. Information is important.

As for your other point, women who have completed their fertility have more secure options for fertility control. It used to be the case that women could not even get an IUD if she had not had a baby (and this is still contested) and most women or couples who have not had children will not choose sterilization. In addition, in many states even today, a young woman can’t get access to contraception without parental consent if she has not had a baby or isn’t married. Point being — the longer women or couples postpone their fertility/marriage/family formation, the longer they have to deal with trying to not get pregnant using less secure contraceptive methods, assuming they are having sex. And while you might reply that all women with an unintended pregnancy have access to abortion, abortion is not readily accessible to all women due to constraints of geography and cost — and some women simply do not feel that abortion is an acceptable option, even if they do not want to give birth. That’s an important reason why public health efforts to develop safe long-acting reversible contraceptives and make them available are important.

LikeLike

It appears Dr. Cohen is not willing to give credit to the CDC (and state agencies) targeted work against teen birth, and assigning all credit to the general trend of all women having birth at a later age. This is a blatant propaganda against programs that have actually worked.

In 1991, the U.S. teen birth rate was 61.8 births for every 1,000 adolescent females, compared with 29.4 births for every 1,000 adolescent females in 2012. The 2013 data is available but has not been yet published, and I estimate it to be closer to 28.75.. This is nearly a a drop of 55% from 1990 to 2013 and is much higher rate of reduction than the increase in the age of mothers.

Teenage child birth unduly impacts the Hispanic and black communities. However, from 1991 to 2012, for the Hispanic community, the teen birth rate fell from 116 to 46; and for the black community, it fell from 100 to 44. Even from 2007, the drops have been steep, Since 2007, the teen birth rate has declined by 34% for Hispanics, compared with declines of 24% for blacks and 20% for whites. The white teen birth rates have declined from 42 to 20. The high income countries have a teen birth rate close to 19, and is comparable to white birth rates in US. As such, more work has to be done in the poorer communities to get to the CDC 2015 target of 20 for the nation as a whole.

Reduction of teenage births, and single mother births (married or cohabiting with partner) are uncool projects for the liberal university establishmentarians, but they are workable tools for poverty reduction.

LikeLike

There is typo above; instead of 28.75 for 2013, “The birth rate for teens aged 15-19 declined 10% in 2013 to 26.6 births per 1,000 women, yet another historic low for the nation, with rates declining for both younger and older teenagers to record lows”

There is no easy way to show that this 10% reduction to simply people postponing childbirths. 20 will be attained reached by 2015 or 2016. It is due to the hard work of a number of faceless bureaucrats..

LikeLike

The intent is not to alienate Dr. Cohen, but just one more point: Teen birth reduction has had significant impacts on high school graduation rates, and women in colleges and workforce. For those who point to stubborn poverty rates, my question is what would the poverty rates be at 100+ teen birth rates? This did not happen in a vacuum, by itself, as some would like us to believe.

In my mind, the government battle against teen childbirths is a significant successful program that stands with unleaded gasoline, low sulfur diesel, auto safety improvements, anti-smoking campaigns, anti alcohol program (while driving) in significantly improving outcomes.

LikeLike

It’s also the other way around: expanding opportunities for women encourage postponement of (and reduction in) fertility.

LikeLike

Focusing your attention on 2007-2013, please notice that the recession has played havoc on opportunities for men and women alike. However, the women of color who have the least expansion of opportunities, have shown the greatest reductions in teen pregnancies. Hence, I do not hold that the two explanations, namely, economic expansion of opportunities, and large scale postponement of child birth, are sufficient to explain 60% reduction of teen child birth rates between 1991-2013.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on The Life Of Von and commented:

Birth tends….

LikeLike