The people who make up these things drive me bananas.

NPR launched a new series on “millennials” yesterday, called “New Boom,” with this dramatic declaration: “There are more millennials in America right now than baby boomers — more than 80 million of us.”

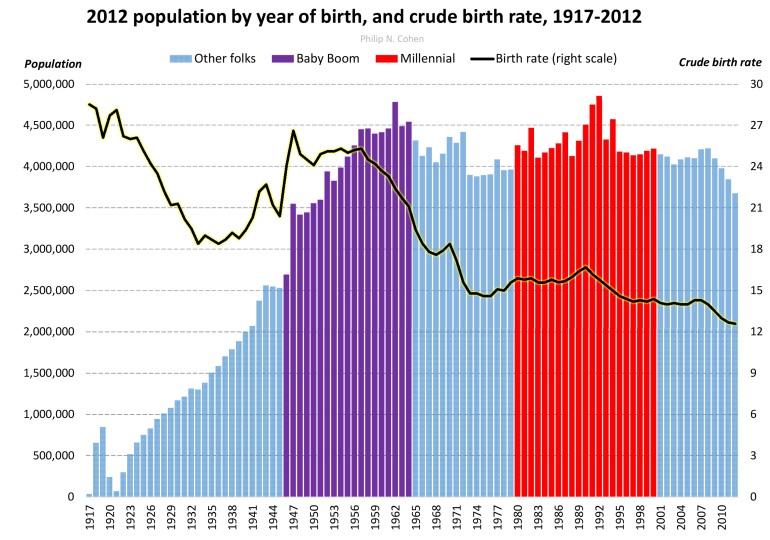

The definition NPR gives for this generation is “people born between 1980 and 2000.” And it’s true there are more than 80 million of them. In fact, there are 91 million of them, according to the 2012 American Community Survey data you can get from IPUMS.org.* That’s OK, though, because there are only 76 million Baby Boomers, so the claim checks out.

But what’s a generation?

The Baby Boom was a demographic event. In 1946, after the end of World War II, the crude birth rate — the number of births per 1,000 population — jumped from 20.4 to 24.1, the biggest one-year change recorded in U.S. history. The birth rate didn’t fall back to its previous level until 1965. That’s why the Baby Boom went down in history as 1946 to 1964. Because that’s when it happened.

This figure shows the number of living people by birth year, and the crude birth rate recorded in each year, using the NPR definition of millennials (in red), compared with the baby boom (purple):

Even with population growth I reckon the people born in the years 1946-1964 might outnumber the self-promoting millennials if not for the weight of mortality pulling down the purple bars. But if the young NPR reporters want to brag about outnumbering a generation that is starting to lose its older members to old age (and who are, after all, their parents), then I guess the shoe fits.

The Baby Boom was not a generation. It was a cohort, “a group of people sharing a common demographic experience” (in this case birth during the same period). That demographic event happens to have lasted 18 years, which is unfortunate because that may have contributed to the tendency to declare “generations” of similar lengths.

The Pew Research people, who do lots of interesting work on social change that uses generational concepts, use these slightly different definitions for four generations: Silent Generation, born 1928-1945; the Baby Boom Generation, born 1946-1964; Generation X, born 1965-1980; Millennial Generation, born 1981 and later (Pew says “no chronological endpoint has been set for this group,” which is awkward because if they’re really still going, the oldest are 33 and they have children that are the same generation as themselves**). Ironic, isn’t it, that Pew constructs “Generation X” as the shortest of the four (some generation, a mere 16 years!) before declaring them “America’s neglected ‘middle child.’”

Real generations rarely have starting and ending points on a population level. Populations usually just keeping having births every year in smooth patterns of increase or decrease without discrete edges, so generations overlap. Even in families it gets hard to nail down generations once you start moving horizontally; siblings born many years apart are in the same generation, but the cousins get all confused.

Meaningful cohorts, on the other hand, can be defined all over the place, such as: the people who graduated college during the Great Recession, people who introduced the Internet to their parents, and so on. These are not generations.

In 2010, when crisis was really in the air, I was on the NPR show The State of Things in North Carolina, discussing the Baby Boom (no audio online). After attempting to clarify the difference between a generation and a cohort, I offered this dramatic example of a cohort — people born in 1960 specifically:

So if you were born in 1960, graduated college in 1982, and entered the labor force in the middle of an awful recession, then managed to pull some kind of career together, got married and divorced, by the 90s it was time to be downsized already for the first time, you’re 40 in 2000, and it’s time for the dot-com bubble, you’re out of your job again, and here you are ready for your retirement, finally, you’ve been left in your own 401(k), having to put together your own pension, and of course now that’s in the tank and your house isn’t worth anything. So that insecurity and instability is really imprinted this group. We talk about the 60s, and civil rights and antiwar, and great music and everything, but that’s seeming like a long time ago now for people who are looking at retirement.

I don’t know if anyone actually had that experience, but it seems likely.

Anyway, if people really want to keep using these generation labels, and it seems unlikely to stop now given the marketing payoff from naming rights, than that’s the way it goes. But please don’t ask demographers to define them.

Notes

* This is a little different from the population estimates the Census Bureau produces, which are coded by age rather than year of birth. I use the ACS data because they report year of birth, and because it’s easier. The differences are very small.

** Thanks to Mo Willow for pointing this out.

“Real generations rarely have starting and ending points on a population level. Populations usually just keeping having births every year in smooth patterns of increase or decrease without discrete edges, so generations overlap.”

Exactly. I have always been confused as to why we talk about members of “generations” as having meaningful similarities with each other and why we draw the boundaries so arbitrarily.

LikeLiked by 2 people

“Many writers have used the succession of cohorts as the foundation for theories of sociocultural dynamics. This approach has been aptly labelled “generationism,” because the writers mistakenly transfer from the generation to the cohort a set of inappropriate associations. Some generationists maintain that there is a periodicity to sociocultural change caused by the biological fact of the succession of generations at thirty-year (father-son) intervals. There is no such periodicity. Other generationists develop a conflict theory of change, pitched on the opposition between the younger and the older ‘generations’ in society, as in the family. But a society reproduces itself continuously. The age gap between father and son disappears in the population at large, through the comprehensive overlapping of life cycles. The fact that social change produces intercohort differentiation and this contributes to inter-generational conflict cannot justify a theory that social change is produced by that conflict. Generationists have leaped from inaccurate demographic observation to inaccurate social conclusion without supplying any intervening causality. All these works suggest arithmetical mysticism, and the worst of them, as Troeltsch said, are ‘reine Kabbala’” (Ryder 1965:853).

LikeLiked by 2 people

Good points! Thanks for sharing. If we don’t use the outdated generation labels, how else would we define these differences?

LikeLiked by 1 person

I heard that story on NPR, too, and I consciously thought of myself as old since I thought something like, “Are they really bragging that there are more of them? Kids these days.” Also in that story, they took credit for inventing social media, because message boards, the internet and Myspace didn’t exist before Facebook.

Gen X FTW.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I love NPR, but I hate being clumped into categories. It’s very convenient, but really? I honestly didn’t know that I was part of Generation X. And, on top of that, I’m the “neglected middle child.” Jeez.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Interesting! As a person born in 1981 I’ve seen my year included in the Gen X list and Millennial. There was an interesting article somewhere that I will never find again, about 1981 being a between year- not really this or that and I really agreed. I have always related to a more Gen-X culture, but not completely. I do think there are cultural imprints from a bulk of years. Would people born in 1962- 1965 or so be really having that different of an experience than a 1960’s ‘cohort’? No categories are perfect.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wow! I feel a little more educated now! I’ve always wondered what defined generations and from your explanation lol I think I’m still confused at their unlogical reasoning. But I appreciate you clarifying that is confusing 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on Engineer Marine Skipper and commented:

#people

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think generations in social demographics are for more complicated than in family or social scenarios where groups of people are just organised into ages instead of ‘generations.’

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on Bluestone Scribe's Blog and commented:

I enjoyed this quite a bit!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on pelgris and commented:

Culturally I would say a generation lasts +or- 5 years. Those at the outer edges may share cultural touchstones and thus identity with other generations. While those towards the center will identify with those within their own group more readily. When you start examining those further out you see that ideas transmitted by popular culture differs sufficiently to discern generations. Of course, if we go further back to when media and thus what allows culture to be transmitted was slower to reach enough people to reach enough mass to be considered a generation, we see a shift in the time frame. Indeed without media or a strong tradition of iterent storytelling, this concept of generation becomes thin. But for the purposes of modern(read 100 to 120 years) cultural shifts +/- 5 years works well.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I and my siblings were born from 59 to 64. We often find ourselves unable to identify with baby boomers. We are on the edge.

LikeLike

Great points!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very interesting post, will definitely be referring back to this. Good point about the awkwardness regarding the millenials having “no chronological endpoint,” though I suspect that some decades from now they’ll probably retroactively place an endpoint at something like 2010.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Something to think about…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Nice job. Liked the graph – 1921 dip begs a discussion.

A boomer.

LikeLiked by 1 person

What a great example of the missteps accompanying humanity’s inexplicable desire to label, to categorize, to put people in a box.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Good points! I was born in 1981 so I consider myself in both the Gen X and Millennials.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I”m still confused. I know what it is in a family (my brothers and I are in the older generation, our kids are in the younger generation). But I don’t know what it is at the population level. I now know what it’s not — it’s not a cohort. But I don’t know what it is.

This seems to be a case where the technical scientific term has crossed over into general use and in the process had its meaning changed. I’m going to remix and overdub my old Who records so that Pete and Roger don’t sound so ignorant: “Talkin’ ’bout my c-c-c-cohort.”

LikeLike

I think an interesting way to look at the charts is to look at what events changed perception on the part of the parents ( in the usa!)…for example I consider gen X to start with people born after president Kennedy assassination and end with those born after John Lennon was killed…those were big events in the collective psyche of groups of people looking at the future with the media available to share the experience in real time shaping perception as parents as to what their children will endure….the time period of the fall of the iron curtain seemed to create hope…I would expect that 9/11 would create some effect ( remembering the parents here are gen x and fairly cynical) perhaps the change recently is simply parents or the idea of being one is so uncertain (constant war on terror and uncertain economies) choose to wait things out because the is no watershed moment

for any collective psyche to embrace and the popular media is fragmented because tool of the internet forces power to be diffused

LikeLike

Happily I was born on the planet Earth the same as everyone else. Breaking people into groups is one of the root causes for discrimination.

LikeLike