Here is the latest version of this essay.

Eric Kaplan, channeling Francis Pharcellus Church, writes in favor of Santa Claus in the New York Times. The Church argument, written in 1897 and barely updated here, is that (a) you can’t prove there is no Santa, so agnosticism is the strongest possible objection, and (b) Santa enriches our lives and promotes non-rationalized gift-giving, “so we might as well believe in him.” That’s the substance of it. It’s a very common argument, identical to one employed against atheists in favor of belief in God, but more charming and whimsical when directed at killjoy Santa-deniers.

All harmless fun and existential comfort-food. But we have two problems that the Santa situation may exacerbate. First is science denial. And second is inequality. So, consider this an attempted joyicide.

Science

From Pew Research comes this Christmas news:

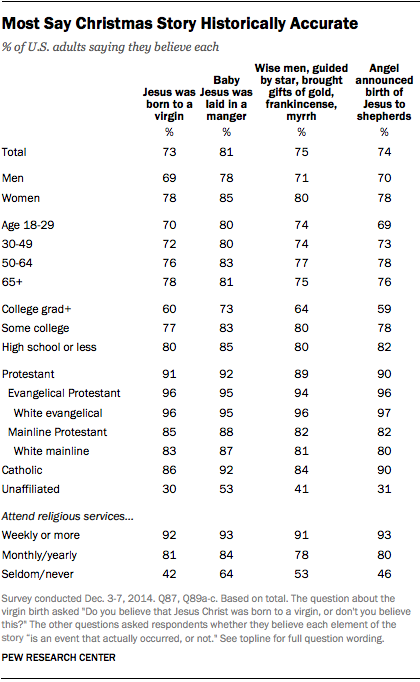

In total, 65% of U.S. adults believe that all of these aspects of the Christmas story – the virgin birth, the journey of the magi, the angel’s announcement to the shepherds and the manger story – reflect events that actually happened.

Here are the details:

So the Santa situation is not an isolated question. We’re talking about a population with a very strong tendency to express literal belief in fantastical accounts. This Christmas story is the soft leading edge of a more hardcore Christian fundamentalism. For the past 20 years, the General Social Survey GSS has found that a third of American adults agrees with the statement, “The Bible is the actual word of God and is to be taken literally, word for word,” versus two other options: “The Bible is the inspired word of God but not everything in it should be taken literally, word for word”; and,”The Bible is an ancient book of fables, legends, history, and moral precepts recorded by men.” Those “actual word of God” people are less numerous than the virgin-birth believers, but they’re related.

Using the GSS I analyzed the attitudes of the “actual word of God” people (my Stata data and work files are here). Controlling for their sex, age, race, education, political ideology, and the year of the survey, they are much more likely than the rest of the population to:

- Agree that “We trust too much in science and not enough in religious faith”

- Oppose marriage rights for homosexuals

- Agree that “people worry too much about human progress harming the environment”

- Agree that “It is much better for everyone involved if the man is the achiever outside the home and the woman takes care of the home and family”

This isn’t the direction I’d like to push our culture. Of course, teaching children to believe in Santa doesn’t necessarily create “actual word of God” fundamentalists. But I expect it’s one risk factor.

Children’s ways of knowing

A little reading led me to this interesting review of the research on young children’s skepticism and credulity, by Woolley and Ghossainy (citations below were mostly referred by them).

It goes back to Margaret Mead’s early work. In the psychological version of sociology’s reading history sideways, Mead in 1932 reported on the notion that young children not only know less, but know differently, than adults, in a way that parallels social evolution. Children were thought to be “more closely related to the thought of the savage than to the thought of the civilized man,” with animism in “primitive” societies being similar to the spontaneous thought of young children. This goes along with the idea of believing in Santa as indicative of a state of innocence.

In pursuit of empirical confirmation of the universality of childhood, Mead investigated the Manus tribe in Melanesia, who were pagans, looking for magical thinking in children: “animistic premise, anthropomorphic interpretation and faulty logic.”

Instead, she found “no evidence of spontaneous animistic thought in the uncontrolled sayings or games” over five months of continuous observation of a few dozen children. And while adults in the community attributed mysterious or random events to spirits and ghosts, children never did:

I found no instance of a child’s personalizing a dog or a fish or a bird, of his personalizing the sun, the moon, the wind or stars. I found no evidence of a child’s attributing chance events, such as the drifting away of a canoe, the loss of an object, an unexplained noise, a sudden gust of wind, a strange deep-sea turtle, a falling seed from a tree, etc., to supernaturalistic causes.

On the other hand, adults blamed spirits for hurricanes hitting the houses of people who behave badly, believed statues can talk, thought lost objects had been stolen by spirits, and said people who are insane are possessed by spirits. The grown men all thought they had personal ghosts looking out for them – with whom they communicated – but the children dismissed the reality of the ghosts that were assigned to them. They didn’t play ghost games.

Does this mean magical thinking is not inherent to childhood? Mead wrote:

The Manus child is less spontaneously animistic and less traditionally animistic than is the Manus adult [“traditionally” here referring to the adoption of ritual superstitious behavior]. This result is a direct contradiction of findings in our own society, in which the child has been found to be more animistic, in both traditional and spontaneous fashions, than are his elders. When such a reversal is found in two contrasting societies, the explanation must be sought in terms of the culture; a purely psychological explanation is inadequate.

Maybe people have the natural capacity for both animistic and realistic thinking, and societies differ in which trait they nurture and develop through children’s education and socialization. Mead speculated that the pattern she found had to do with the self-sufficiency required of Manus children. A Manus child must…

…make correct physical adjustments to his environment, so that his entire attention is focused upon cause and effect relationships, the neglect of which would result in immediate disaster. … Manus children are taught the properties of fire and water, taught to estimate distance, to allow for illusion when objects are seen under water, to allow for obstacles and judge possible clearage for canoes, etc., at the age of two or three.

Plus, perhaps unlike in industrialized society, their simple technology is understandable to children without the invocation of magic. And she observed that parents didn’t tell the children imaginary stories, myths, and legends.

I should note here that I’m not saying we have to choose between religious fundamentalism and a society without art and literature. The question is about believing things that aren’t true, and can’t be true. I’d like to think we can cultivate imagination without launching people down the path of blind credulity.

Modern credulity

For evidence that culture produces credulity, consider the results of a study that showed most four-year-old children understood that Old Testament stories are not factual. Six-year-olds, however, tended to believe the stories were factual, if their impossible events were attributed to God rather than rewritten in secular terms (e.g., “Matthew and the Green Sea” instead of “Moses and the Red Sea”). Why? Belief in supernatural or superstitious things, contrary to what you might assume, requires a higher level of cognitive sophistication than does disbelief, which is why five-year-olds are more likely to believe in fairies than three-year-olds. These studies suggest children have to be taught to believe in magic. (Adults use persuasion to do that, but teaching with rewards – like presents under a tree or money under a pillow – is of course more effective.)

Richard Dawkins has speculated that religion spreads so easily because humans have an adaptive tendency from childhood to believe adults rather than wait for direct evidence of dangers to accumulate (e.g., “snakes are dangerous”). That is, credulity is adaptive for humans. But Woolley and Ghossainy review mounting evidence for young children’s skepticism as well as credulity. That, along with the obvious survival disadvantages associated with believing everything you’re told, doesn’t support Dawkins’ story.

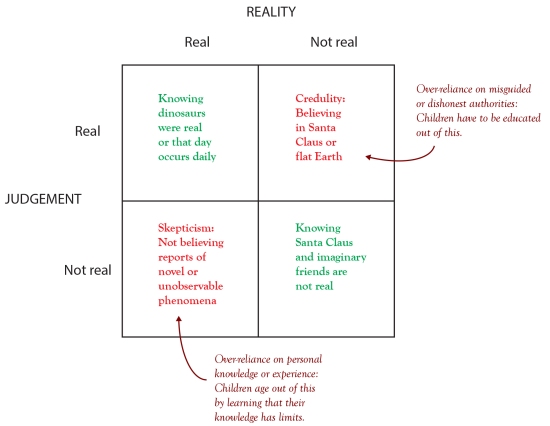

Children can know things either from direct observation or experience, or from being taught. So they can know dinosaurs are real if they believe books and teachers and museums, even if they can’t observe them living (true reality detection). And they can know that Santa Claus and imaginary friends are not real if they believe either authorities or their own senses (true baloney detection). Similarly, children also have two kinds of reality-assessment errors: false positive and false negative. Believing in Santa Claus is false positive. Refusing to believe in dinosaurs is false negative. In this figure, adapted from Woolley and Ghossainy, true judgment is in green, errors are in red.

We know a lot about kids’ credulity (Santa Claus, tooth fairy, etc.). But, Woolley and Ghossainy write, their skepticism has been neglected:

It is perplexing that a young child could believe that his or her knowledge of the world is complete enough to deny the existence of anything new. It would seem that young children would understand that there are many things that exist in the real world that they have yet to experience. As intuitive as this seems, it appears not to be the case. From this perspective, development regarding beliefs about reality involves, in addition to decreased reliance on knowledge and experience, increased awareness of one’s own knowledge and its limitations for assessing reality status. This realization that one’s own knowledge is limited gradually inspires a waning reliance on it alone for making reality status decisions and a concomitant increase in the use of a wider range of strategies for assessing reality status, including, for example, seeking more information, assessing contextual cues, and evaluating the quality of the new information.

The “realization that one’s own knowledge is limited” is a vital development, ultimately necessary for being able to tell fact from fiction. But, sadly, it need not lead to real understanding – under some conditions, such as, apparently, the USA today, it often leads instead to reliance on misguided or dishonest authorities who compete with science to fill the void beyond what we can directly observe or deduce. Believing in Santa because we can’t disprove his existence is a developmental dead end, a backward-looking reliance on authority for determining truth. But so is failure to believe in germs or vaccines or evolution just because we can’t see them working.

We have to learn how to inhabit the green boxes without giving up our love for things imaginary, and that seems impossible without education in both science and art.

Rationalizing gifts

What is the essence of Santa, anyway? In Kaplan’s NYT essay it’s all about non-rationalized giving — for the sake of giving. The latest craze in Santa culture, however, says otherwise: Elf on the Shelf. According to Google Trends, interest in this concept has increased 100-fold since 2008. In case you’ve missed it, the idea is to put a cute little elf somewhere on a shelf in the house. You tell your kids it’s watching them, and that every night it goes back to the North Pole to report to Santa on their nice/naughty ratio. While the kids are sleeping, you move it to another shelf in house, and the kids delight in finding it again each morning.

Foucault is not amused. Consider the Elf on a Shelf aftermarket accessories, like these handy warning labels, which threaten children with “no toys” if they aren’t on their “best behavior” from now on:

So is this non-rationalize gift giving? Quite the opposite. In fact, rather than cultivating a whimsical love of magic, this is closer to a dystopian fantasy in which the conjured enforcers of arbitrary moral codes leap out of their fictional realm to impose harsh consequences in the real life of innocent children.

Inequality

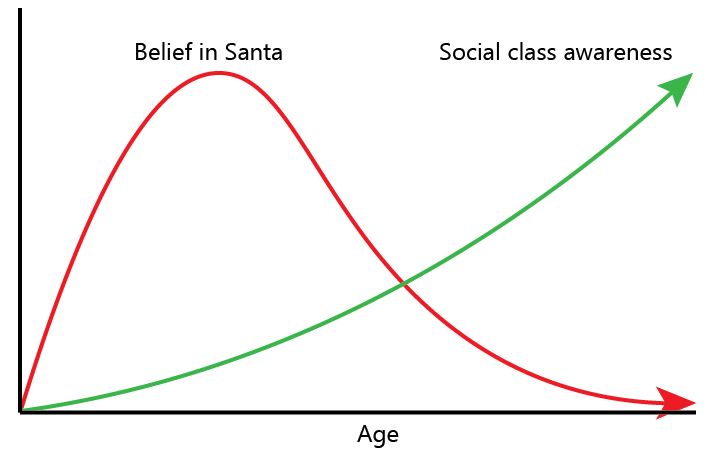

What does all this mean for inequality? My developmental question is, what is the relationship between belief in Santa and social class awareness over the early life course? In other words, how long after kids realize there is class inequality do they go on believing in Santa? Where do these curves cross?

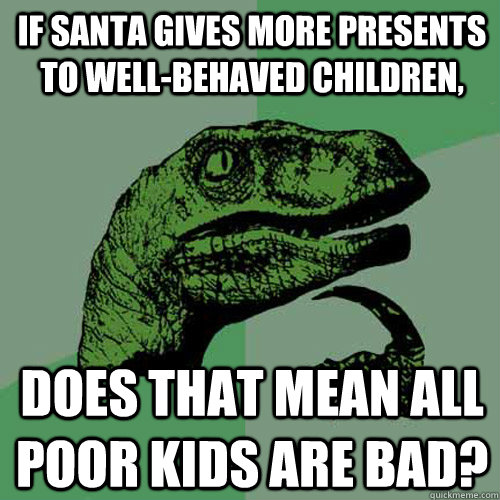

Beyond worrying about how Santa rewards or punishes them individually, if children are to believe that Christmas gifts are doled out according to moral merit, than what are they to make of the obvious fact that rich kids get more than poor kids? Rich or poor, the message seems the same: children deserve what they get. Of course, I’m not the first to think of this:

Conclusion

I can’t demonstrate that believing in Santa causes children to believe that economic inequality is justified by character differences between social classes. Or that Santa belief undermines future openness to science and logic. But those are hypotheses.

Between the anti-science epidemic and the pervasive assumption that poor people deserve what they get, this whole Santa enterprise seems risky. Would it be so bad, so destructive to the wonder that is childhood, if instead of attributing gifts to supernatural beings we instead told children that we just buy them gifts because we love them unconditionally and want them — and all other children — to be happy?

The question I am left with is, how is it possible that the vast majority of Americans are such staunch believers. I have two 12-year olds, pretty much like all 12 year olds I know, who are probably located in the top-US-ten percent in terms of skepticism regarding religious dogma. Max Weber’s old explanation of American’s adherance to faith is outdated. Any new explanations?

LikeLike

Reblogged this on The Life Of Von and commented:

Culture produces credulity….

LikeLike

yes yes yes yes this is great.

LikeLike

Really fantastic treatment; couple two-tree things to add.

James Carrier (I think) suggests that the idea of the ideal, pure, free gift only appears in societies with significant market integration, because people are trying to countervail growing individualism. I don’t agree (it’s just as likely that increasing inter-group trade makes people more altruistic and more likely to deliberately celebrate altruism), but it’s an interesting idea.

And it’s maybe not surprising that three year olds don’t invent hypotheticals to explain long chains of causation, but that children do more and more as their brains develop (those Western observations seem to corroborate Mead’s indigenous observations). As a context-free cognitive process (whether we attribute causes to moral rights and wrongs or physical unobservables like “force”), generating hypotheticals is the basis of any theory – magical or scientific.

The “inventing infantile stories” was an anthropological prejudice (and according to Mead’s falsification, not more), and you are just reproducing it by painting conservatives with that brush.

LikeLike

Is there a difference between sociology and left-wing activism?

LikeLike

Sociology without left-wing activism is like a fish without a bicycle.

LikeLike

Let’s get real. Lacking any skills useful to society or to anyone else for that matter, a plague of left-wing parasites (living off the tax-payers’ dime) befouling our exceptionalist Judeo-Christian ethos inhabit academe.Trust in these leeches and/or the “science” they sling is of far greater pernicious consequence to western civilization in particular and to the human than belief in Santa or the tooth fairy.

LikeLike

You never know how people are going to react when they find out Santa isn’t real.

LikeLike

I’m wondering about this Mead account though: Children do seem to engage in magical thinking very easily–e.g., something bad happens to me because I’m bad, etc. They also seem very prone to certain kinds of fears that make them really susceptible to certain supernatural ideas–like fear of the dark, monsters under the bed, etc. I remember believing completely physically impossible things as a kid that I just made up right there and then but afterward they would seem real–.e.g, I thought that inside a tree in front of my house was an entire civilization. Pretend/imaginary play gets very blurred with real events and when a 5 year old comes home from school it can be hard to decipher what really happened v. what they were playing at recess. So they are suggestible, maybe–but they are not the reasonable, detached experiencers of the world that Mead is describing, I don’t think.

LikeLike

Thanks. I agree with your description, but you’re describing children (yourself or others) who are 5 years old or older – plenty old enough to be affected by their culture and material circumstances.

LikeLike

Yet, my son had imaginary friends by age 2. Isn’t that indicative of magical thinking?

LikeLike

When I was in school my sociology professor cautioned us, “Don’t take sociology too seriously; it’s not like it’s a real science.”

LikeLike

Sociology is politically homogenous, but economics is theoretically and methodologically homogenous.

Dogma is the result of the structure of the academy (lots of revolving doors and entry barriers instead of intellectual competition). Leftism is not in itself the problem with modern scholarship, and Philip and other lefties I know are on balance gracious, dedicated, and very smart people.

If we’re going to go in circles like, “you’re ideological,” “no you!” then there’s no reason to be here.

LikeLike

My comment has nothing to do with ideology and everything to do with the silliness of much of academia.

LikeLike

The Pew “estimate” is obviously at least twice as high as it should be. I searched for technical information on the phone poll, but there are no response rates given. Biblical fundamentalism has declined somewhat over the last 30 years that GSS has kept track, and rejection of belief in the bible is also up. Notably, fundamentalism impacts inequality directly, by restricting vocabulary and scientific literacy, stifling educational attainment, negatively impacting occupational trajectories (especially for women), and lowering income and wealth (see Keister and Sherkat, 2014, Religion and Inequality, Cambridge for a review). Much of this happens because of how fundamentalist religion perverts sexuality and family relations, often leaving devotees and their children at the bottom rung of the stratification hierarchy.

LikeLike

The GSS word of God question is much more hardcore and all-encompassing than the Pew question about discrete well-known Jesus events. It doesn’t surprise me they get a much higher number.

LikeLike

Actually, the specificity of those events should yield at best a number in line with biblical fundamentalism. At best. It’s a huge overestimate because it’s not a scientific survey. It’s not even an estimate of the population parameter. It’s a constructrion based on some opinions of people who responded within three days for a survey during the height of Holiday chaos. Then, they “adjust” it to fix for population characteristics…yeah….right.

LikeLike

I tremble for my country when I reflect that Santa is just.

LikeLike

I’m late to this party, but loved this piece — my daughter is just 4, and while I found the whole Santa ritual very very fun for nostalgic charm I have wondered several times what I am going to say if / when the premise “Santa judged you very good, ergo lots of presents” intersects for her with “many children have hardly anything”. I already found myself avoiding the topic because they both come up around the holidays — lots of charity drives, for example. She was very curious about a dancing bag of groceries at the mall (someone in a costume for a food drive) — what was that all about? Clearly it seemed to her to be part of “Christmas hubbub” and I wasn’t quite sure what to say because of the logical inconsistency between “actual need” and “magical plenty”.

For a less sociological, more anthropological take, Lévi-Strauss’s “Father Christmas Unwrapped” is fascinating on why we adults go to such elaborate, weird lengths to coax children into that particular set of magical beliefs (I can’t find a downoadable version; republished in 1993 in _Unwrapping Christmas_ edited by Daniel Miller, 38–51. Oxford: Clarendon Press.)

LikeLike

Nice article! I found this blog through your article debunking the misleading reportage that Black women are the most educated cultural group in America – also great stuff! I live in Australia and feel that within most social class groups the notion of Santa rationalising his gift-giving according to naughty or nice binary is, gladly, not really an important part of the myth, or at least it’s not widely encouraged outside of the individual family’s interpretation of Santa. I imagine some parents still use it as a way to enforce moral behaviour but I believe there is a genuine emphasis on non-rationalised gift-giving at Christmas. Personally I have no problem with rewarding my kids achievements using gifts from Mum and Dad or sometimes restricting special treats/experiences for what we regard to be very poor behaviour, but Santa himself does not judge. To some extent this approach to parenting is only made possible by my relative privilege (the ability to actually buy some of the gifts that the kids want), but refusing to link Santa’s gift-giving with an evaluation of good or bad behaviour is an interpretation available to parents, even though it leaves inequality of gifts unexplained. I often wonder how my benevolent Santa will intersect with my children’s developing understandings of social class and inequality. As you hypothesise, I imagine the discovery of Santa as myth will inevitably come along with the realisation of socially produced inequality. As a child (as far as I can remember) I was aware of the mythical nature of Santa precisely because his gifts clearly reflected the economic circumstances of the different nuclear families within our extended family. Our cousins got some outrageously expensive stuff. I feel that the Santa myth is pretty benign though if all it does is reflect existing social structures (like everything else in the world, real or mythical) via the relative quality/quantity of largely unimportant, material gifts. In fact it may prove to be quite educative. However, Santa’s use as a form of moral conditioning is much more problematic as it rationalises poverty in a way that way that encourages social reproduction regarding measures of self-worth and expectations for kids from different social classes.

LikeLike

It’s easy to have Santa without undermining empathy for the poor. (1) Avoid much talk about the whole naughty/nice idea. (2) Have Santa give one gift plus stocking stuffers. All other gifts come from parents.

Poor children get less because their parents can’t afford gifts, therefore we help them out by buying gifts for them. Worked with my son.

I always understood Santa to be a concrete stand-in for God because children can’t grasp the more abstract concept. Santa is certainly concrete – you sit on his lap, ask for gifts, and, if you are good, you get your reward. Basically the same deal as God (pray, get miracles & go to heaven if good).

LikeLike