Using phones while driving is dangerous and should stop. But the focus on this issue distracts us from other dangers in driving (which have — you’d never believe from the news — declined rapidly in recent decades). And it distracts us from the broader danger of relying on motor vehicle transportation.

I dwell on this subject because it offers lessons beyond its substantive importance (see all the posts under the texting tag). Today’s lesson is about conflicts of interest in the news media.

The AAA Foundation for Traffic Safety published a study of about 1,700 moderate or severe car crashes in which people ages 16-19 were driving. To identify possible causes of the crashes, they used cameras and motion sensors in the cars, and analyzed the seconds before each crash. The headline result probably should have been that 79% of the crashes occurred when teens were driving too fast. But that’s apparently not news, so the AAAFTS and all the news media reporting the story focused on the fact that 59% of the crashes showed distraction as a likely cause.

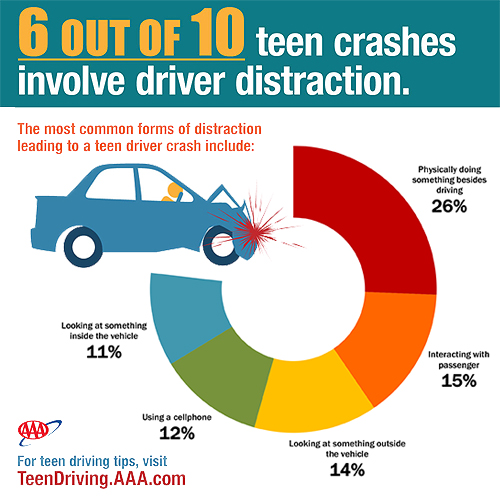

The report website highlighted the data on distractions, and that’s reasonable. One of their findings is that distractions in their survey account for a greater proportion of accidents than are reported officially — something we’ve assumed but have had trouble establishing empirically. So that’s useful. They used this graphic:

By this accounting, phones were involved in 12% of crashes, second only to interacting with passengers. But this is an artifact of the way the categories are binned. And a lot of smaller categories are left out of the figure, such as eating and drinking (2%), operating vehicle controls (3%), looking at another vehicle (4%), or smoking-related distractions (1%). (Note also that one crash can have multiple related distractions, but they don’t report the overlaps so you can’t do anything about them.)

So I redid the categories. I don’t see why eating and drinking should be a separate category from grooming, or why singing/dancing should be separate from adjusting the radio. So I made a new category called “physically doing something besides driving,” which includes eating or drinking, using an electronic device (besides phone), grooming, reaching for an object, smoking-related activity, operating vehicle controls, and singing/dancing to music. Also, for some reason their figure lists “looking at something outside the vehicle” but only includes “attending to unknown outside vehicle” in that category. I added two other types of distraction to that category, “attending to another vehicle” and “attending to person outside” — bumping up the outside distraction substantially.

Here’s my new version of their figure based on the same data (from table 13 in the report). It’s more comprehensive but uses fewer categories:

Now cellphones are fourth. So that’s a lesson about using arbitrary category collapsing and then ranking the categories. (This happens all the time with occupations, for example, where people say, “The top X occupations…” but the occupations reflect different levels of granularity.)

Anyway, back to cellphones

The New York Times reporter Matt Richtel won a Pulitzer Prize for his reporting on distracted driving. And he published a book — A Deadly Wandering — that tells the tragic story of a driver who killed someone while he was texting. Unfortunately, he is prone to hyping the problem of texting, which his audience is unfortunately prone to fixating on. I previously pointed out that, on the website promoting his book, his publisher uses an extremely wrong statistic, claiming that texting “continues to claim 11 teen lives per day.” He has mentioned this statistic (or its variant, that texting kills more teens than drunk driving) on Twitter, and also in media appearances. I pointed out that this number is more than all the teens killed in motor vehicle accidents, so it’s obviously baloney. I emailed Richtel about this, and he told me he would “get it fixed.” I emailed the publisher. I emailed the Times. I emailed the Diane Rehm show. No one changed anything. Cellphone crashes are like child abuse: people will believe any statistic about how bad it is and attack anyone who’s skeptical.

Of course I don’t want to minimize the problem of distracted driving, and there’s nothing wrong with telling people it’s dangerous. And it’s not my area of expertise. So I’ve only given the issue a few hours. But playing into a public hysteria about a very narrow, behaviorally-driven problem, rather than exposing the systemic problem that it reflects, is not good.

And now that Richtel is selling a book about texting, he’s got a conflict of interest — if he hypes the problem in his NYT stories, he makes more money. So here’s the NYT headline on his story:

And this is his lead paragraph:

Memo to parents: Distracted driving by teenagers is riskier than previously thought, particularly when it comes to multitasking with a cellphone.

Again, it is true the report finds cellphone distraction causes more accidents than police reports have shown — so this is not irrelevant — though, of course, even with the new accounting they still cause orders of magnitude less than Richtel’s own promotional site claims. But mentioning phones in the headline sets the NYT apart from most of the coverage of this report:

- Washington Post: “AAA: 58 percent of teens involved in traffic crashes are distracted”

- ABC News: “Distractions a Problem for Teen Drivers, AAA Study Finds”

- Houston Chronicle: “Distraction a factor in 6 in 10 teen driver crashes”

- Chicago Tribune: “Distracted driving a key contributor to teen crashes, study shows”

On my first page of Google News searches, only the LA Times also mentioned phones: “Teen drivers distracted by cellphones, talking in most crashes.”

Who cares?

Some people who are tired of me complaining about this think you can’t have too much hype about safe driving, so who cares? But the distraction matters. The evidence that phones are a fundamental cause — a social cause — of accidents and deaths is very weak, although they are certainly the proximate cause in many cases. But we don’t have randomized controlled trials to test the effects of phones. I suspect the people crashing while futzing with their phones are mostly the same people who would be crashing for some other reason if cellphones didn’t exist.

When I look at the video compilation the AAA put out to accompany their report — which mostly shows teens crashing while using their phones — I am struck by what terrible drivers they are. They look down for three seconds and drive straight off the road without noticing. In contrast, I routinely see people driving on the freeway completely absorbed in their phones — driving obnoxiously slowly but using their peripheral vision to keep going straight. They are at grave risk of an accident if something crosses their path or traffic stops, but they’re not veering all over the road. Their slow speed probably mitigates their risk of crashing. I AM NOT RECOMMENDING THIS, I’m just saying: bad drivers cause accidents, and if you give them a phone they’ll use it to cause an accident.

Did you know teen driving fatalities have fallen by more than half in the last decade? (During that time incidentally, teen suicides have risen 45%.) Did you know that, from 1994 to 2011, mobile phone subscriptions increased more than 1200% while the number of traffic fatalities per mile driven fell 36% (and property-damage-only accidents per mile fell 31%)? Don’t count on Matt Richtel to tell you about this.

And yet, of course, thousands of people die in car accidents every year in the U.S. — at rates higher than the vast majority of other rich countries. But as long as people drive, there will be bad drivers. If we really cared, we would replace individual cars with mass transit (or self-driving cars) — putting transport in the hands of computers and professionals. Nothing’s perfect, of course, but preventing car accidents isn’t rocket science, and blaming a systemic problem on the individual behavior of predictably error-prone drivers doesn’t seem likely to help.

Reblogged this on rennydiokno.com.

LikeLike

Reminiscent of Gusfield’s work on drunk driving.

LikeLike

Great post. I wish I had read it early, when I was discussing in another forum the sensibility of fining people talking on cellphones.

LikeLike

Singing/dancing should be separate from adjusting the radio. The former is primarily a mental distraction; the latter is also a visual distraction. In the latter, the drivers attention is focused in a way that their field of vision doesn’t really see outside.

Good job illustrating the point you were trying to make – the ethical risks of using data to support pre-conceived ideas. Glass houses, stones.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Reblogged this on oluyoyelarthyphat.

LikeLiked by 1 person

If we really cared, we would replace individual cars with mass transit (or self-driving cars) — putting transport in the hands of computers and professionals.

Leaving aside self driving cars, because they practically speaking don’t exist yet, there is no mass transit alternative to densely interconnected network.

And yet, of course, thousands of people die in car accidents every year in the U.S. — at rates higher than the vast majority of other rich countries.

If we really cared, we’d have driver training as rigorous as Germany’s, and pay much more attention to bad driving as opposed to fast driving.

Except the latter is far more lucrative.

LikeLike