First some context, then some data.

Ruth Graham has a story in the Boston Globe about how liberals and conservatives — researchers as well as policy advocates — are starting to agree that marriage is good and policy should promote it. I’m quoted, but apparently as an example of what Andrew Cherlin refers to as someone standing at “a line some liberal sociologists won’t cross, that line of accepting marriage as the best arrangement.” This is part of a spate of stories in which journalists look for a new consensus on marriage. Previous entries include David Leonhardt in the New York Times saying liberals are wrong in attributing the decline of marriage to economics alone, and Brigid Schulte in the Washington Post reporting that Isabel Sawhill has given up on “trying to revive marriage.” The narrow consensus in policy terms involves a few things, like increasing the Earned Income Tax Credit and reducing marriage penalties in some parts of the safety net, along with trying to improve conditions at the low end of the labor market (see this Center for American Progress report for the liberal side of these policies).

From teen births to marriage promotion

The idea of a cultural revival of marriage has been the futile bleat of the family right for decades, most recently retooled by David Blankenhorn. And in recent years these ideologues have taken to using as an example the supposed success of the cultural intervention to reduce teen pregnancy, to show how we might increase marriage and reduce nonmarital birth rates. This has been a common refrain from Brad Wilcox, quoted here by Graham:

As evidence of his optimism, Wilcox points to teen pregnancy, which has dropped by more than 50 percent since the early 1990s. “Most people assumed you couldn’t do much around something related to sex and pregnancy and parenthood,” he said. “Then a consensus emerged across right and left, and that consensus was supported by public policy and social norms. … We were able to move the dial.”

I think that interpretation is not just wrong, it’s the opposite of right, as I’ll explain below.

I don’t know of any evidence that cultural intervention affected teen birth rates. Cultural intervention effects are different from cultural effects — of course cultural change is part of the trend in marriage and birth timing, but the commonly cited paper showing an apparent effect of 16 and Pregnant on teen births, for example, is not evidence that the campaign to reduce teen pregnancy was successful. There was a campaign to end teen pregnancy, and teen pregnancy declined. I think the trend might have happened for the same set of reasons the campaign happened — the same reasons for the decline in marriage and the shift toward later marriage. The campaign was one expression of shifting norms toward women’s independence, educational investment, and delayed family formation.

The myth of teen pregnancy

I’ve been trying to say this for a while, and it doesn’t seem to be taking. Maybe I’m wrong, but I’m not giving up yet. So here goes again.

If you had never heard of teen pregnancy, you would see the decline in births among teenagers as what it is: part of the general historic trend toward later births and later marriage. I tried to show this in a previous post. I’ll repeat that, and then give you the new data.

First, I showed that teen birth trends simply follow the overall trend toward later births. Few births at young ages, more at older ages:

It doesn’t look like anything special happening with teens. To show that a different way, I juxtaposed teen birth rates with the tendency of older women (25-34) to have births relative to younger women (20-24). This showed that teen births are less common where older births are more common:

In other words, teen births follow general trends toward older births.

Today’s data exercise

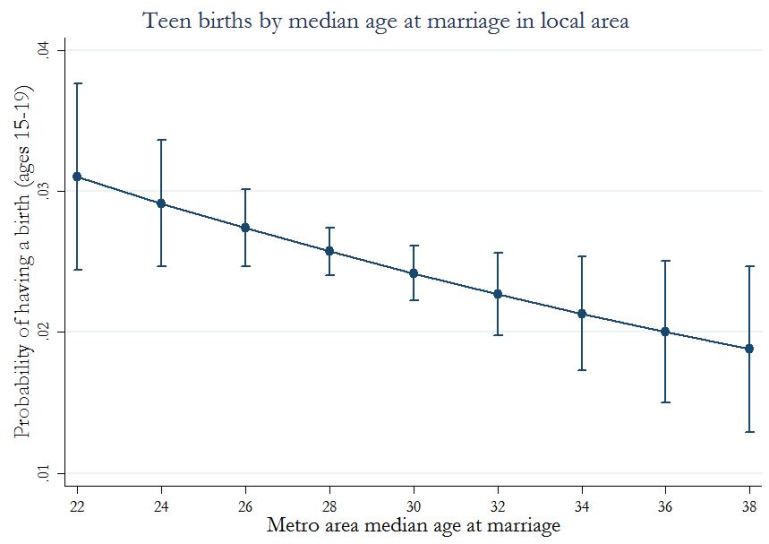

Here’s a more rigorous (deeper dive!) into the same question. I show here that teenage women are less likely to have a birth if they live in place with higher age at marriage, and if they live in a place with lower marriage rates. That is, lower teen births go along with the main historical trend: delayed and declining marriage.

So if you think declining teen births are an example of how a policy for “cultural” intervention can reverse the historical tide, you’re not just wrong, you’re the opposite of right. The campaign to reduce teen births succeeded in doing what was happening already. This is not a model for marriage promotion.

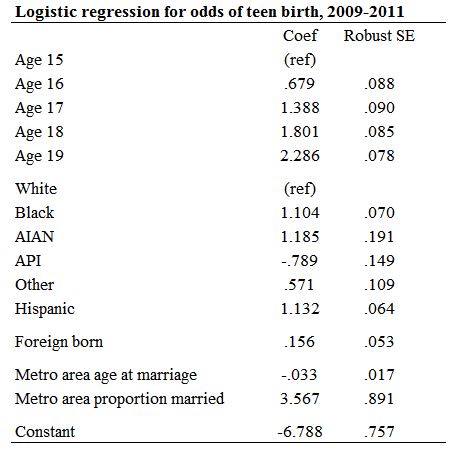

Here’s what I did. I used the 2009-2011 American Community Survey, distributed by IPUMS.org. For 283 metropolitan areas, accounting for 73% of all U.S. 15-19 year-old women, I calculated the odds of a teenage woman reporting a birth in the previous year, as a function of: (a) the median age of women who married in that area in the previous year, and (b) the proportion of women ages 18-54 that are currently married in that area. I adjusted these odds for age, race/ethnicity, and nativity (foreign born). I didn’t adjust for things that are co-determined with births among teens, such as marital status, education, and living arrangements (in other words there is plenty of room to dive deeper). All effects were statistically significant when entered simultaneously in a logistic regression model, with robust standard errors for metro area clustering.*

The figures show probabilities of having a birth in the last year, adjusted for those factors, with 95% confidence intervals:

To summarize:

- Teen births are a myth. There are just births to people ages 13 to 19.

- Teen births have fallen as people increasingly delay childbearing and marriage. Falling teen births are simply part of the historical trend on marriage: rising age at marriage, declining marriage rates.

- The campaign to prevent teen births coincided with the trends already underway. Any suggestion that this could be a model for promoting marriage — that is, a policy that goes against the historical tide on marriage — is hokum.

- There remains no evidence at all to support any policy intervention to promote marriage.

* Well, the age at marriage effect is on significant at p=.054 (two-tailed), but my hypothesis is directional — and that cluster adjustment is brutal! Anyway, happy to share code and output, just email me. Here’s the regression table:

If anything, the evidence resoundingly suggests the cultural message (abstinence only until marriage) didn’t work. The more rigorous evaluation studies did not find these programs accomplished much (and had many negative outcomes), while other work shows that decline can be attributed to an uptick in contraceptive use. Improvements in contraceptive use (both in consistency & use of more efficacious methods) can be attributable on the micro-level to improved knowledge and education but at the macro level likely to the reasons you discuss, as the adoption of better contraception is not limited to teens.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Karen;

While teenage births have declined, non-marital births among women in their twenties has skyrocketed. so much so that we now have a 40% national illegitimacy rate.

Apparently all that contraception education didn’t work either.

LikeLike

Birth rates are also down for early 20-something’s. The shift from marital births to nonmarital births is a related but different story than changes in birth rates. I would not entirely discount social and cultural change but not for the way that Wilcox and his ilk argue

LikeLike

Thank you for this column! I am constantly amazed at the continuation of mythology about teen pregnancy and birth, particularly the arrogant assertion that two teenagers in the back seat of a car are going to stop what they are doing because of something some teacher in school said.

There are some bigger truths out there that have been backed up time and time again. First, if you want an intervention to work, it will take much more than a high school classroom. Whether it is comprehensive sex education or abstinence education, as they are offered in American schools the effect is negligible. The few programs that really do work are comprehensive not just in the amount of sexual knowledge, but comprehensive as in centering sex as just one of many aspects of life. Effective programs offer work experience, encourage academic growth, communication skills, physical fitness, and improved family dynamics. They empower the whole teen, but they cost time, begin early in the student’s career, and (gasp!) cost taxpayers money.

And that’s the point here. Empowered teens are more likely to make the choices we hope they will. Is that really so surprising?

LikeLike

First off, Figure 1 is leading since you are plotting only the percentage change; we do not know what the share of each age group in the total births is, and hence we cannot conclude that the reduction in teen births is made up by single mothers giving birth at a later age. That point cannot even be proven unless you follow up on the teen age cohort that delays birth, but goes ahead and gives birth as a single mother at a later age.

The second wrong point that this essay propagates is that the people were anyway delaying births, and so the campaign to delay teen births did not matter. Teen births and older mother births (as single mother or otherwise) are two different things. A very great majority of teen births are births to single mothers, and the fathers had little or no immediate role to play owing to the lack of income or ability to form families. A majority of single mother child births beyond the teen age groups, is by choice, and have, significant contribution by fathers, as cohabitants, or as sources of economic, moral and material support. The false equivalency between teen births and older women births should be put to rest forever, and the false idea that government had no role in delaying teen births.

The third, and last objection to this whole essay is the idea that social and economic mores have no roles; this is a bias of statisticians who see no role for causation. The 1980s (and beyond) economic liberalization and free trade agreements have played havoc upon the lives of the lower classes, and had a nonlinear feedback on family formation and inequality. As the jobs available to the “below-college” educated has decreased, both, affordable family formation has decreased, and family inequality has increased. This has been amplified by the role of immigration, which now has bitten back the children of the first generation immigrants. Only a MArxist analysis of the two factors can explain the delay in family formation (which is esssentially an inability to form families). Making a time series analyses and saying that this has been happening over years, in my opinion, is a fruitless contribution.

LikeLike

Vijay;

If family formation is negatively influenced by a paucity of jobs, then illegitimacy would have skyrocketed during the Great Depression when poverty was widepread and there was no government social safety net. It didn’t. In fact, illegitimacy began to rapidly climb during the 1960s, when good paying factory jobs still existed and when wealth inequality was not so large, and has continued to climb through good economic times and bad.

The prime reason for family breakdown still appears to be cultural.

LikeLike

I think you missed two points of my reply. Economic short term cycles (and corresponding job losses) make no difference on the long term graph of marriage /child birth. You cannot use a recession or depression to show an impact of childbirth and family formation, because of the long term nature of the process vis-a-vis short term economic cycles.

However, the impact of free trade/liberalization and immigration is very long term; they preferentially impact the lower classes who are educated at HS level or below. Second, the impact on men is more than women because they take less service sector jobs. With less men to pay for family formation, women take the lead, and children are located more in single mother families. Third, the existence of multiple races and immigrants exacerbate the family-formation gap and college-educated/below college educated gap, and accelerate the family inequality gap.

The word “cultural” is a coded word; I interpret it as meaning “people of colr cant make families” and need to be rejected. If there were more industrial jobs and less immigration, people of color can form families as good as anyone else.

LikeLiked by 1 person

While it’s true that the decline in teen pregnancies/births coincides with other trends related to marriage, explaining other changes in teen sexual behavior is a trickier issue. Teens have become more sexually conservative since the early 1990s. A smaller proportion are having intercourse. Fewer are currently sexual active. Fewer report having had sex with multiple partners. And when teens do have sex, they tend to wait until older ages, and are more inclined to use condoms. Conversely, for unmarried young adults, a greater proportion are having sex. More report multiple partners. And unintended pregnancies are on the rise.

Your old pal Mark Regnerus attributes changes in teen sexual behavior to an emerging sexual morality among middle class youth, which is future-oriented, self-focused, and risk aversive. This morality involves trading the “higher” pleasures of vaginal intercourse for “low risk” sex (e.g., oral sex, porn, masturbation), and not for religious reasons but to safeguard the future. (Paradoxically, Hamilton and Armstrong make a similar class-based argument about hooking up among young adults. They argue that for more privileged women in college, hooking up, which often includes sexual intercourse and with multiple partners, is part of a class-based strategy to avoid early marriage and family formation and to meet their educational and career goals).

Conversely, Barbara Risman and Pepper Schwartz attribute changes in teen sexual behavior to shifts in gender relations. They argue that the decline in sexual risk behaviors among teens is the result of girl’s increased influence in intimate relationships and the increased power of girls in their sexual encounters. Girls are more likely to push for sex within relationships, however defined, and in that context are better positioned and are more likely to insist on safe sex.

Of course, the fear of disease is probably another factor. Considerable evidence suggests that people have changed their sexual habits because of the perceived risk of contracting STDs.

LikeLike

A full summary:

http://www.guttmacher.org/pubs/gpr/17/3/gpr170315.html

LikeLike

I don’t follow in this. Maybe because i’m not american so i’m missing some of the background if this ongoing argument, even if I often follow it for personal interest. So. What do you mean by “teenage pregnancy don’t exist”? And let me explain: as a demographic concept they do follow into the general category of “pregnancy” (or birth rate) for that age group. Ok. BUT: as a polical concept, they exist in the fact pregnancy in teenage year likely disurpts education and the general life to which a teenager should be entitled. I guess when we do development program, for example, we (as western, “developed” people) strongly insist that early marriage and early pregnancy are a problem. I fail to see why it shoudn’t be a problem here?

Now: if what you’re saying is that pregnancy among teenagers is not falling for some miraculous cultural intervention, i agree. It surely isn’t a product of the “abstinence education”. I don’t get the “non existant” part as a general statetment, or maybe are you saying the rates are so low and falling anyway so is not a political concern and not a priority? I guess that may be true, too. Still, i wouldn’t say it “doesn’t exist” as a general political/social concept. One could say that, ideally, you would want to lower the birth rate to near zero for teens, but not so much for older age groups (and this can be debatable, but let’s say we still worry about the replacement level of the TFR or something close to that–i know that’s much more of a concern here in old EU than in the US). So, just asking for a clarification on this. On the marital/non marital births thing–this is just nonsense, it’not worth a comment. France has over 50% of the births out of marriage, no one is crying.

LikeLike

(i blame typos and errors to the autocorrect!)

LikeLike

Reblogged this on uchechioma blog.

LikeLike

I am looking for current statistics that shows married teens (ages between 13-17) are more likely to start a family in high school….if they were not pregnant before. Do you know any?

LikeLike

Here’s my question; I would buy the teen pregnancy shift as a part of a larger shift toward later-in-life pregnancies overall, except I attribute those later pregnancies to a choice. Women are *choosing* to start families later. Teen pregnancy (and I don’t have any statistics here, but based on what I would consider common sense) is nearly never planned…so I’m unclear on how those two things could possibly be related. How could women choosing to start families later in life impact women who are becoming unintentionally pregnant (regardless of age)?

LikeLike