“People are saying” that we need to think about how to interpret, and possibly punish, past racism, relative to current racism. This is as much about the meaning of “past” as it is about the meaning of “racism.” It’s about individual suspected racists — specifically leading Virginia Democrats — and about the intersection of individual and institutional racism, as preserved and displayed in yearbooks, as in this photo of the University of Illinois KKK chapter in 1924, which included representation from each fraternity on campus:

Politicians are a special case, because their authority is in theory dependent on the legitimating consent of the governed. On the other hand are regular individuals, for whom being labeled a racist is among the harshest reputational penalties we have. More important than individuals is how they add up to groups, organizations, and institutions.

Then there are powerful individuals representing institutional interests, such as Charles Murray, who spent decades on the dole of non-profit organizations funded by the foundations of the rich (in other words, you). He built an extremely influential career blaming poverty on inborn deficiencies (“born lazy“) among the Black poor and providing scientific cover for dismantling government support for meeting their needs.

Why burn that cross

In the grand scheme maybe it doesn’t matter whether Charles Murray (now an emeritus at age 76) is, or was, racist in his heart — his work was racist in its effects (White supremacist terrorist Dylann Roof parroted Murray in his rationale for murdering Black people in church.) However, he and his defenders have always impugned those who assign racist motives to his work. He clearly believes in a biological racial hierarchy in genetic intelligence, which is an old-fashioned definition of racism. The new scientific racists, a coalition that includes Murray, defends itself from that charge by claiming it’s not racist if it’s true, and it has fallen to human geneticists to debunk their claims. The charge of racism has always weakened the legitimacy of Murray and his compatriots, and narrowed their reach. As I think it should — you don’t need to know what was in his heart to think his work was terrible, but it’s relevant.

Shawn Fremstad reminded me that Murray and his friends burned a cross in 1960, which seems like a good thing to dredge up during racist-yearbook week. Here is the very cursory story, in a 1994 New York Times profile for the release of his book The Bell Curve.

While there is much to admire about the industry and inquisitiveness of Murray’s teen-age years, there is at least one adventure that he understandably deletes from the story — the night he helped his friends burn a cross. They had formed a kind of good guys’ gang, “the Mallows,” whose very name, from marshmallows, was a play on their own softness. In the fall of 1960, during their senior year, they nailed some scrap wood into a cross, adorned it with fireworks and set it ablaze on a hill beside the police station, with marshmallows scattered as a calling card.

[Denny] Rutledge recalls his astonishment the next day when the talk turned to racial persecution in a town with two black families. “There wouldn’t have been a racist thought in our simple-minded minds,” he says. “That’s how unaware we were.”

A long pause follows when Murray is reminded of the event. “Incredibly, incredibly dumb,” he says. “But it never crossed our minds that this had any larger significance. And I look back on that and say, ‘How on earth could we be so oblivious?’ I guess it says something about that day and age that it didn’t cross our minds.”

This is a very incomplete story, which doesn’t even tell us who first told the tale of the cross burning, or what reason that person gave for it, or how they picked the location. But reading this, my sociological opinion is that “dumb” is likely a dodge; and my sociological question is, if they had no idea of the “larger significance” of cross burning, in 1960, why do it? There were lots of dumb things to do. My sociological approach to this question is to investigate the context in which this cross burning occurred, both in the social environment and in Murray’s life course trajectory.

The fall of 1960, the beginning of Murray’s senior year of high school, was when he would have been applying to Harvard, which he went off to in 1961 (he was a history major). It was also a time when cross burning was in the news a lot, including in Iowa.

The 1960 Census recorded 15,000 people in the idyllic cross-burning town of Newton, where Murray’s father was a Maytag executive. And there were only 22 Black people recorded in Jasper county (where Newton is the principal city). Does this mean race was not an issue in the minds of Murray’s gang? I’m very doubtful. Blacks were a noticeable, and noticeably growing, presence in Iowa cities, including Des Moines, just 30 miles from Newton. (The new Interstate 80 hadn’t connected Newton and Des Moines yet, but sections of it were already built west of Des Moines, and it was penciled in on the map.) During the 1950s the state’s nonwhite population increased about 70%, from 17,000 to 29,000. In fact, the 1950s were the biggest decade for Black migration to Iowa. Almost all of them lived in urban areas, including Des Moines. The city had 209,000 people, of which 10,700 (5%) were nonwhite (mostly Black) by 1960.

So, do you think a 1960 White executive’s family would have heard anything about the nonwhite population of the nearest city nearly doubling in the previous decade? Did aw-shucks Murray and his pool hall buddies know about all that big city stuff?

We have some other evidence from which to speculate. Murray traveled around the state, and even the country, in his high school years. He was on Newton High School’s “Crack Debate Team” that won several statewide tournaments, including one at the University of Iowa in Iowa City in April 1960. And that summer the debate team roadtripped to California, courtesy of the Chamber of Commerce, for a national tournament. (What did they debate, anyway?)

Des Moine Register, June 15, 1960.

Des Moine Register, June 15, 1960.So in 1960 Murray was the son of an executive, and a debate team champion, traveling the state and country, and applying to Harvard, while living in the next county over from a city with a booming Black population. Oh, and it was 1960: the year civil rights protesters staged sit-ins in dozens of cities across the south, from February through April.

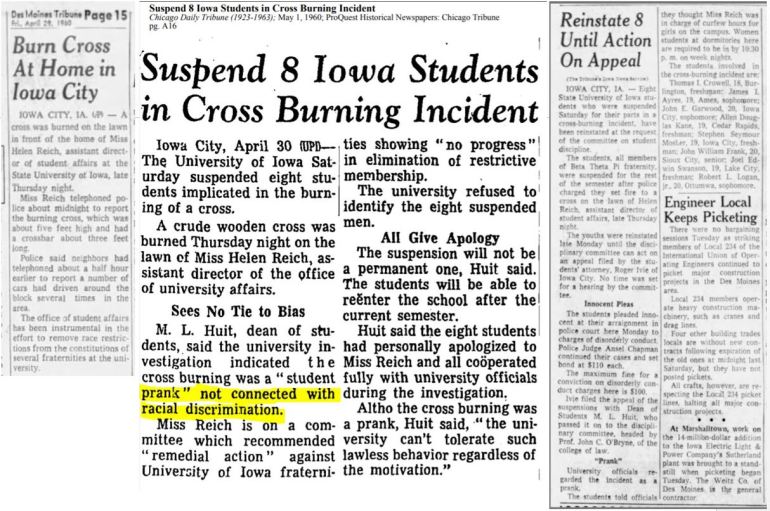

By my count there were 55 articles in the Des Moines Register/Tribune archives mentioning cross burning during his high school years, 1955 to 1960. In fact, there were a number of stories about an Iowa City incident, where in April 1960 (yes, that April 1960), eight Beta Theta Pi frat brothers burned a cross on the lawn of the assistant director of student affairs, whose office was “instrumental in the effort to remove race restrictions from the constitutions of several fraternities at the university.” After briefly suspending the men, the university declared it a “prank” and reinstated them on probation:

Maybe it was a pure coincidence having nothing to do with race that the eight frat brothers burned a cross in their “prank.” But why a cross? Also, it was a few weeks after students picketed stores right there in Iowa City to support the sit-ins.

I see a possible parallel between the frat boys and the cross burning by Murray’s marshmallow gang. The story is they had no idea it was about race; decades later, this is the story they recite. Some key White adults helped keep the narrative from getting out of hand. I’d bet the incident didn’t make it into Murray’s Harvard admissions packet, either in his personal essay or in the form of a criminal record. Even though there was “talk” in town the next day.

And they went on about their lives. Murray isn’t an elected office holder, and may be retired. Maybe it’s water under the racist.

Incidentally, I noticed that one of the University of Iowa cross-burning frat boys, Joel E. Swanson, seems to have gone on to become a state district court judge. (I don’t know what happened to their disorderly conduct charge.) He was a freshman in 1960, got his law degree at the University in 1967, while serving in the National Guard, and worked as a lawyer in his home town of Lake City, eventually became a judge and then retiring in 2012. Also, they have recipes.

Anyone who parrots eugenic theories from the 1930’s in support of arguing that black people are inherently less intelligent is at the very least a poor scholar, but having read the Bell Curve I think there was more to it than that. There are few essays I enjoyed more than the New York Times Book Review’s expose’ of Murray’s sources. His book is still held up as a reason for school reform, despite the fact that scholars quickly debunked it.

LikeLike